Lemkin on Genocide, Prevention, and the Law

The Lemkin Program is dedicated to continuing Lemkin’s broad vision of genocide prevention as a never-ending process of building peace through the rule of law, the historical recognition of victims, and scholarship and practice that is guided by an ethics of the human universal to stand up to the powerful forces of group pride and group hate.

Raphaël Lemkin

Originator of the word “genocide” and leader of the global movement to outlaw genocide at the United Nations

“Like all social phenomena, genocide represents a complex synthesis of a diversity of factors; but its nature is primarily sociological, since it means the destruction of certain social groups by other social groups or the individual representatives …

Raphaël Lemkin did not define genocide as an act of mass killing. He saw genocide as a type of conflict that sometimes escalated into direct violence, but not always. In Lemkin’s analysis of genocide, we find a theory of group destruction that involves systems of repression and oppression, direct and indirect violence, structural and cultural violence, a direct link between the economic destruction of targeted groups and their cultural suppression, and the denial of the victims’ right to exist because of their social identity—all in an effort to eradicate group identities from the fabric of society.

Yet, genocide was often committed by people who did not think they were committing genocide, and often held no hate in their hearts. For Lemkin, what made genocide so difficult to prevent was that it involved “countless small and different actions that, when taken separately, constituted different crimes, or sometimes did not constitute a crime at all, but when taken together constituted a type of atrocity that threatened the existence of social collectivities and threatened the peaceful social order of the world.”

… genocide is a gradual process and may begin with political disenfranchisement, economic displacement, cultural undermining and control, the destruction of leadership, the break-up of families and the prevention of propagation. Each of these methods is a more or less effective means of destroying a group. Actual physical destruction is the last and most effective phase of genocide”

— Lemkin, Introduction to the Study of Genocide

Lemkin on Prevention

Because genocide and mass atrocities are complex social processes, prevention is also a social process and equally complex. This means there is no prescription for prevention; but rather genocide prevention involves de-escalating identity-based conflicts, working to dislodge deeply rooted conflicts, and building peaceful, inclusive, and just societies.

True prevention requires a commitment to making and building peace, supporting recognition efforts, and championing inclusive societies that are free of all forms of bias and discrimination, promoting economic justice, encouraging bystanders to become advocates long before the outbreak of direct violence, working to connect victims and the marginalized to local and global networks of solidarity, and striving to create the structural conditions—from the local to the global—that provide all groups and individuals with equal access social, cultural, economic, and political opportunities and rights. Most importantly, for Lemkin, this was underpinned by the rule of law, and the necessity of trans-national social movements to defend the moral authority of international institutions and international law when states begin to repress their own populations.

Genocide prevention work demands a radical vision of reconciliation as something that must occur before genocide occurs, so that conflicts that seem intractable today can be dislodged and de-escalated long before they escalate into genocidal conflicts (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, Chapter 7 and Conclusion).

Lemkin on Genocide

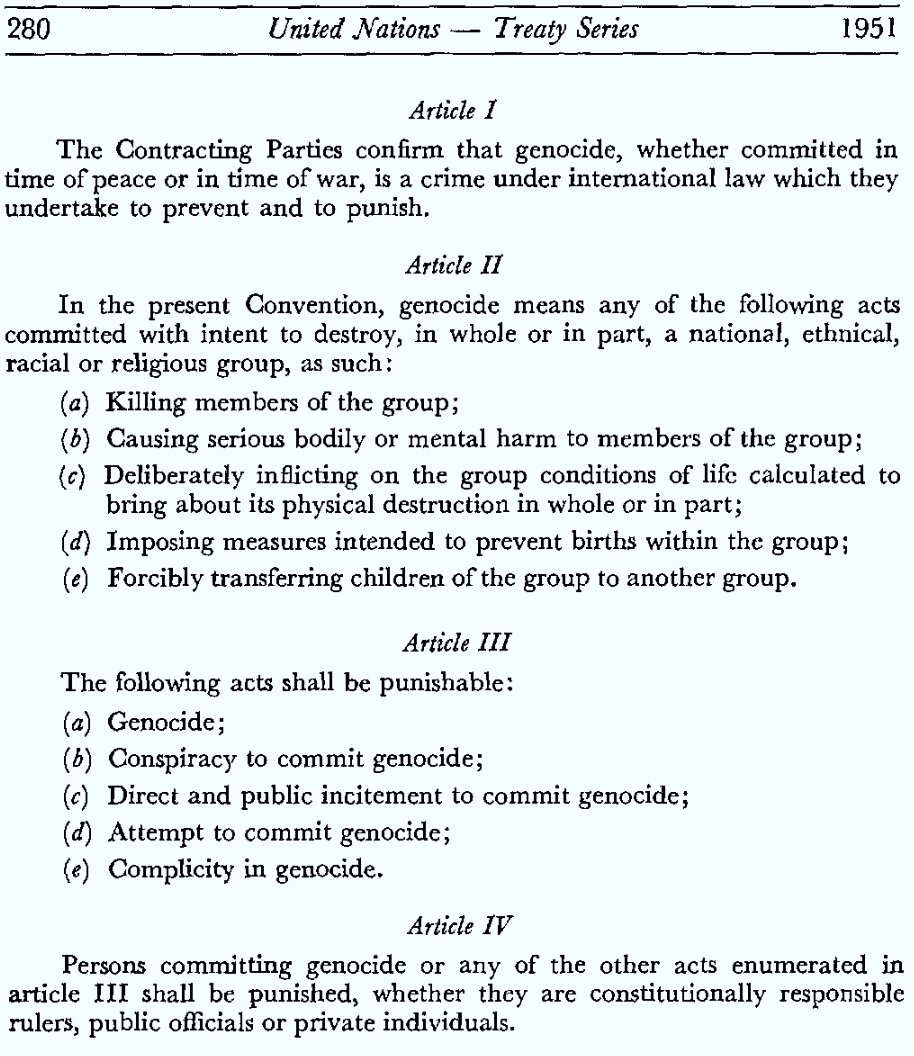

Even though Lemkin led the movement at the United Nations to draft the Genocide Convention, the definition of genocide in the 1948 Genocide Convention was not Lemkin’s definition. Rather, it was a compromise worked out by delegates representing UN member states. Compare the two texts below: the legal definition of genocide in the 1948 Convention, left, and Lemkin’s social scientific definition, on the right, from Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, which was written between late 1941 and early 1943, and published in 1944.

Notice Lemkin’s broad definition of social groups in Axis Rule (his definition of a national group was much broader than our current definitions of nations), and notice how he defines genocide as a colonial process of removing the national patterns of the oppressed and imposing the national patterns of the oppressors. And, finally, notice in both the UN treaty and Axis Rule that genocide can be committed without killing anyone (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, chapter 6).

Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in 1944

Notice Article I of the Genocide Convention defines genocide as a crime of war and peace. This marked a radical expansion of the laws of war, to apply the laws of war during times of formal peace, which effectively made the actions of state security forces against their own populations subject to international law. This was an original position Lemkin outlined in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe.

Notice Article IV does not list states as the responsible parties for genocide, but rather individuals. This was another principle Lemkin outlined in Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Individualizing guilt was crucial to efforts to build peace, Lemkin thought, because it would prevent people in the future from holding entire groups responsible for past crimes and then repeating the very processes of group demonization that fuel genocide. Instead of blaming "the Germans" for the Holocaust, for example, Lemkin believed it was necessary to make clear that it was individuals who made choices to commit, conspire to commit, participate in, be complicit in, or incite genocide.

Lemkin on Nations and Social Groups

In his courses at Yale Law School after the passage of the UN Genocide Convention in 1948, Lemkin taught his broad definition of genocide to his students—in contrast to the definition of genocide in the Genocide Convention. He taught his students that social groups were not primordial entities, and that all categorical distinctions between human beings were not predetermined. He settled on the term “genocide,” he told his class, because the Greek and Sanskrit connotations of the root word “genos” signified a human group that was constituted through a shared way of thinking, not objective relations. The concept of the “genos” Lemkin said, “was originally conceived as an enlarged family unit having the conscience of a common ancestor—first real, later imagined.” It was here, in the “imagined connection” between peoples, where “the forces of cohesion and solidarity were born.” The same forces of group cohesion, Lemkin taught, could also serve as “the nursery of group pride and group hate” that is “sometimes subconscious, sometimes conscious, but always dangerous, because it creates a pragmatism that justifies cold destruction of the other group when it appears necessary or useful” (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, Chapter 7).

The Genocide Convention is Adopted in 1948, UN Archives, New York

“For much of history the fury or calculated hatred of genocide was directed against specific groups which did not fit into the pattern of the state or religions community or even in the social pattern of the oppressors. The human groups most frequently the victims of genocide were religious, racial, national and ethnical, and political groups. But genocide victims could also be other families of mind selected for destruction according to the criterion of their affiliation with a group which is considered extraneous and dangerous for various reasons.

These other groups do not have to be racial or religious groups, but could be groups such as those who play cards, or those who engage in unlawful trade practices or in breaking up unions. Genocide could be conducted against criminals because states today criminalize certain types of subjectivities and families of mind…”

— Lemkin, Introduction to the Study of Genocide

Lemkin on the Law

Lemkin believed the true power of international law was moral and normative, and that international law was strongest when it linked domestic and international legal systems, and inspired the creation of new norms and new moral values in societies around the world. Lemkin firmly believed there was no inherent, universal belief that genocide was wrong. In fact, Lemkin went to great lengths to show just how much the world’s great religious and literary traditions celebrated genocide, and just how much those who committed genocide thought genocide was progress, natural, good, and necessary for securing peace. In other words, the values against genocide were not given in humanity—they had to be created. In this sense, Lemkin saw the law as an instrument of social change, not unlike poetry or art or education. An international law against genocide could be a mechanism for creating new moral values, and infusing those values in societies around the world.

Lemkin had a longstanding belief that world peace could be supported when international law helped reorganize domestic legal codes towards supporting sociological, cultural, political and economic institutions within societies around the world to prevent war and collective violence. In 1932, Lemkin collaborated with his mentor Emil Stanisław Rappaport to draft a the new Polish criminal code. Article 113, which Lemkin wrote, criminalized the production and dissemination of propaganda intended to incite a domestic population toward aggressive war and violence. Just a few years earlier, in 1927, Hersch Lauterpacht had published an influential essay with the Grotius Society, finding that prohibitions on propaganda to incite war were not violations of international law, but could be enshrined in national laws, and even in municipal laws, through reciprocal treaties. Lemkin followed Lauterpacht’s ideas in drafting Article 113, and he claimed the Polish penal code was the first in the world to outlaw propaganda to incite violence. In his commentary on the law, Lemkin articulated a position he never abandoned throughout his entire life: domestic laws could be instruments for international peace, because war and political violence were aspects of state policy that had to first be legitimized domestically (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, chapter 2).

Lemkin’s famous proposal to outlaw “barbarity and vandalism,” which he authored for a League of Nations conference in 1933 on international terrorism, is well known. Less well know, but equally important, is a paper he wrote in 1937 that argued European states were moving toward war, and many of the conflicts between these states could be eased through domestic criminal laws that reflected international ideals. International law should not be thought of as preventing armed conflict by maintaining a balance of power and collective security among states, Lemkin argued. Instead, he suggested, domestic laws of states should be reorganized through international treaties to prevent people within states from participating in the mobilization of war. Between 1937 and 1938, he began research for a massive study on the way the regulation of international payments and financial exchanges were causing conflicts between states—and were being used as instruments of conflict by totalitarian states to harm and undermine the economies of certain populations in other states. Lemkin published this work in French, and incorporated the analysis into Axis Rule in Occupied Europe (see Irvin-Erickson, chapter 2).

Lemkin on the Law as a Source of Peace

Lemkin’s theory of the law drew on the rich tradition of Jewish law, which tends not to view the law as a strict instrument of state control over individuals, nor as something that outlines regulations and punishment for violations (as many people often think about the law today). Instead, Lemkin saw law as a moral and normative force for social cohesion that brought about a shared sense of obligations and duties between people, out of which communities came into existence. The law as such may look different in different societies through history and around the world. Nevertheless, for Lemkin, all human societies had law—even if it took on different forms in different contexts.

Like many who grew up in the “shatterzone of empires” or the “bloodlands,” as historians have characterized Eastern Europe in the early 20th century, Lemkin’s experiences inspired an intense drive to prevent others from suffering the terror he witnessed and survived. In the 1939, he fled the German and Soviet conquest of Poland. In his autobiography, he writes his life was in danger on both sides of the border that quickly divided his country. On the Soviet side, he had been denounced by the Soviet state as an enemy of the revolution for his writings on how the Soviet penal code was an instrument for violently stamping out “enemy consciousness.” On the German side, his life was in danger because he was Jewish—and indeed Lemkin lost almost every member of his family in the Holocaust, and barely escaped German occupied Europe. Proud of his Jewish and Polish heritage, he was pained by watching many of his fellow Poles join the Nazi program to exterminate the Jewish people and cleanse Poland of Jews. Like many Holocaust survivors, Lemkin believed that defending universal human values was the key to preventing the horrors he had suffered, and that the cornerstone of peace was the social and cultural institutions that made societies welcoming of diversity.

After the Second World War, Lemkin sharpened his belief that international law was more than a tool for securing peace by balancing power in international relations and providing collective global security. Instead, he argued, international law could organize the domestic laws of states to prevent societies from mobilizing toward something he called “genocide,” legitimizing universal ideals and translating cosmopolitan sensibilities into the social fabric of those states. In Axis Rule, true to his life’s work, he proposed this international law against this new concept of “genocide” require states to outlaw genocide in their domestic legal codes (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, chapter 4).

Notice that Article V of the Genocide Convention compels states to outlaw genocide under their own national laws.

Notice that Article VI of the Convention invokes an international penal tribunal with jurisdiction over the contracting parties of the treaty—but there was no such court in existence in 1948.

Why does the UN Genocide Convention reference international courts that did not exist when the treaty was drafted?

Lemkin’s papers show that he orchestrated a quid pro quo with the Soviets, the US, and UK to make major compromises in the definition of genocide. They agreed to:

Remove all references to colonization, narrow the protected groups from any social group to only four specific groups, and emphasize that genocide is crime committed only through physical acts — with the exception of “severe mental harm.”

This removed from the purview of the definition of genocide the oppression being committed by the UK, US, USSR and other member states against minorities, indigenous peoples, colonized populations, and class enemies; it essentially legalized attempts to destroy social groups that were not named as protected groups; and it removed from the law the very kinds of indirect and structural violence that were at the core of Lemkin’s expansive understanding of genocide.

They also agreed to:

Name the acts that by which genocide could be legally committed; and include a narrow framing of criminal intent.

The narrowing of the acts that constitute genocide is akin to specifying the four or five ways that murder can be committed—as if it were only murder, legally, if the act was committed this way, and any other way of taking a life was allowed. Focusing on how the act was committed, and not the act itself, removed from the definition of genocide the mass killings and famine the USSR was committing, the mass killings and state terror being committed in European colonies, lynchings and racial terror in the United States, and the forced assimilation and extermination of indigenous peoples in the US, Canada, Sweden, Australia, and New Zealand. All of the delegates on the UN drafting committees openly acknowledged that this is what their home governments were instructing them to do.

In exchange, the Major powers acquiesced and allowed articles V, VI, VIII, and IX to remain in the law—thinking these articles were harmless because there were no such court in existence at that time (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, Chapter 6).

Why did Lemkin orchestrate these trades?

It strikes many as strange and deeply unsatisfactory that Lemkin would have willingly sacrificed his definition of genocide, in such a way. But Lemkin understood that legal definitions of concepts were different than social scientific definitions of concepts, and he felt that a flawed Genocide Convention was better than no Genocide Convention at all. He also understood that international law was always going to be an extremely politicized undertaking that demanded compromise. And, he felt that international law might be a powerful moral and normative force in the world, but the process through which international law came about in the first place was political not moral.

In his autobiography Lemkin writes that these articles he fought to defend would eventually create the legal machinery necessary for international courts and fact-finding missions in the future, so that when the sentiments of the world shifted in the favor of such courts the Genocide Convention would be there, waiting to be used. Lemkin, who died in 1959, never saw any of the international courts he envisioned come into existence, and he died thinking his life’s work had been a failure. But, thirty years after his death, the Genocide Convention was used in 1989 as the vehicle for Trinidad and Tobago to revive efforts to establish an international criminal court to deal with drug trafficking in the Caribbean. And, in 1992, the International Law Commission built a vision for an international criminal court around the only treaty that called for such a court to come into existence: the Genocide Convention, which was “the one instrument in international law that could directly bind the individual and make individual violations punishable.” That summer, UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s famous report, An Agenda for Peace, which is widely considered as establishing the field of peacebuilding, argued that strengthening international law around the Genocide Convention would provide the foundation of an international criminal justice regime that could guarantee global peace between states and within states (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, Chapters 6 & 7).

Secondly, Lemkin thought it was important that states that ratified the Genocide Convention would be compelled to outlaw genocide in their own domestic legal systems, and translate this concept and adapt it to fit local contexts. In the 1950s, he turned his full attention to helping states like Brazil, Egypt, Ethiopia, and Denmark outlaw genocide domestically in a way that made sense for their own societies. Here, too, Lemkin’s efforts payed off long after his death—as domestic laws outlawing genocide played important roles in justice, recognition, and reconciliation efforts in countries like Argentina, Canada, and Cambodia beginning in the early 2000’s (see Irvin-Erickson, Raphaël Lemkin, Chapters 6 & 7).